|

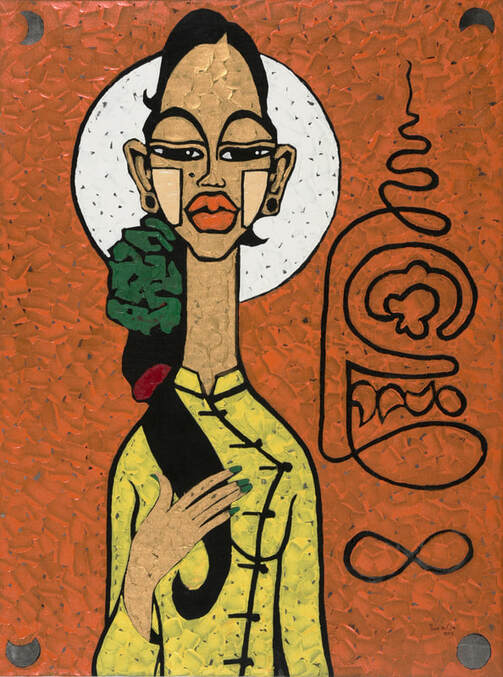

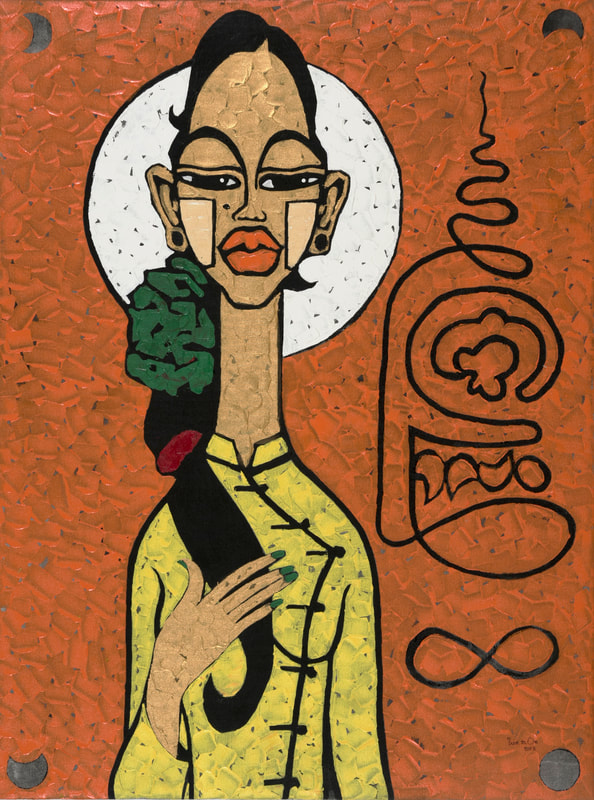

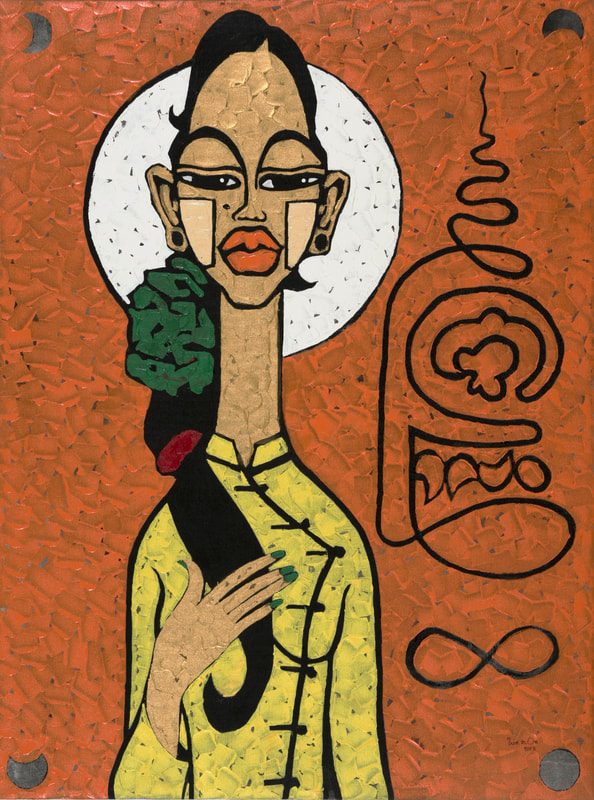

Zwe Mon, Untitled, 2013 Acrylic on canvas 36” x 48” BC2019.03.05

|

This exhibition offers diverse portrayals of women by contemporary artists in Burma (also known as Myanmar) that reflect a politico-cultural milieu in flux between traditional and modern or contemporary impulses. After some fifty years of military rule, extreme censorship, and isolation from the rest of the world, a vibrant artistic scene emerged during a new era inspired by the leadership of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The story of this iconic woman, activist, political leader, former State Counselor, 1991 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who was frequently held under house arrest, continues amid turmoil over her recent arrest and political deposition during the military coup of 2021. The depiction of women by contemporary artists is also an ongoing story, a tale of diverse experiences, perspectives, contemplations, and articulations.

The paintings featured here challenge conventional, traditional images of women in Burmese society. The feminist concept of the “male gaze” in works created by mostly male artists, is also contrasted here with a female expression by a woman artist who gives us another reading of the female body, dress, and bearing. The female portraits—referencing rural settings, symbolic icons, Buddhist spirituality, ordinary life, fashion and beauty, political protest, or tags, cartoons and nudity unimagined and unseen prior to 2010—attest to the rapid changes in the country and in contemporary paintings over the past two decades when Myanmar opened its doors to radical modernity. The paintings range in date from 2006 to 2015 and have been divided thematically to highlight dialogues formed in images of women in traditional, urban, political, and sexual contexts. The artists who created these works are all still living, but some were born before the 1962 military-backed coup orchestrated by then Chief Staff General Ne Win, others after the fall of Socialist Burma and some after the 1988 mass protests for democracy. Their place of birth, education, life experiences, and careers as artists differ considerably. Any artist active between1962 and 2012, however, lived with the restrictions of government censorship. For some, this was devastating, as when Aung Khaing (b. 1945) had an entire show of 120 paintings banned in 1984. Many artists graduated from the State School of Fine Arts in Yangon but struggled to make a living as an independent artist. It has only been since the 2010s that the market, the galleries, the social and political reforms began to open new opportunities for artists to create and show their art. While most of the works displayed here are by male artists, we are fortunate to be able to show Untitled (2013) by Zwe Mon, a woman artist who creates images that represent not just herself, but all Burmese women, and are imbued with a desire to support women against discrimination and sexual exploitation. There are more female artists active today whose voices need to be heard. These paintings arrived at NIU thanks to a generous donation by Ian Holliday, an authority on Myanmar politics and governance active both academically and administratively at the University of Hong Kong where he serves as Dean of Social Sciences, Vice President, and Pro-Vice Chancellor of Teaching and Learning. As works from his Thukhuma Collection, these paintings were also part of an exhibition of contemporary paintings from Myanmar held in the Jack Olson Gallery (School of Art and Design) in 2016. More information about the artists in the Thukhuma Collection and the cultural contexts in which they works can be found in a book published just this year, edited by Ian Holiday and Aung Kaung Myat titled Painting Myanmar’s Transition (Hong Kong University Press). This exhibition was curated by Art History professors Dr. Helen Nagata and Dr. Catherine Raymond. |

In this section, Burmese women are portrayed...

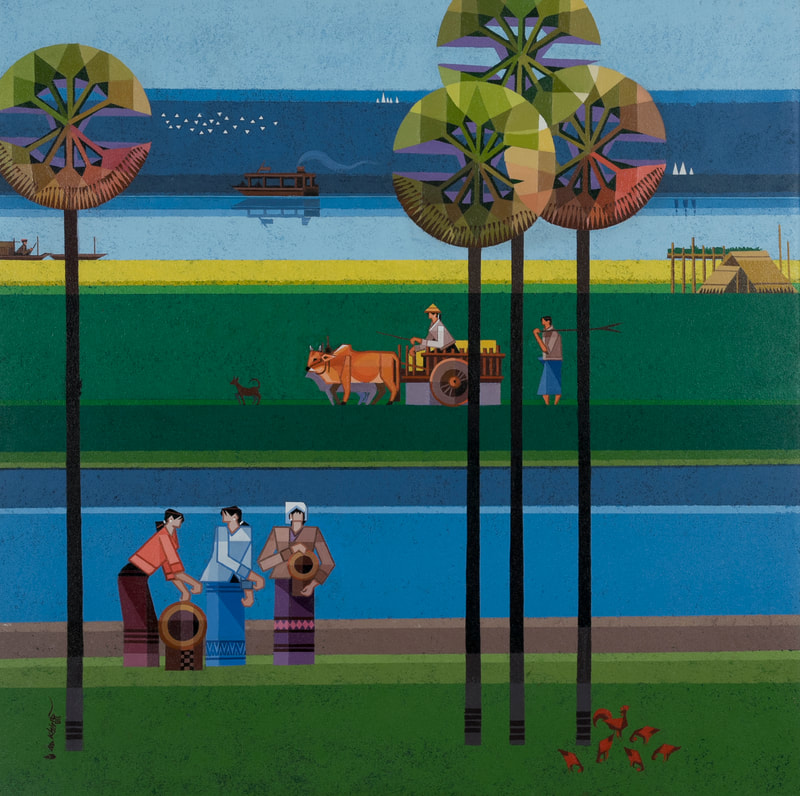

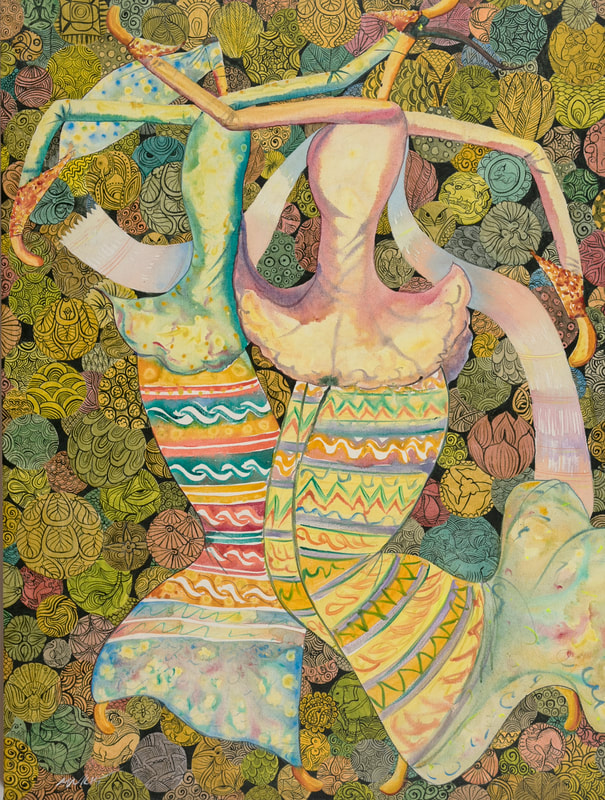

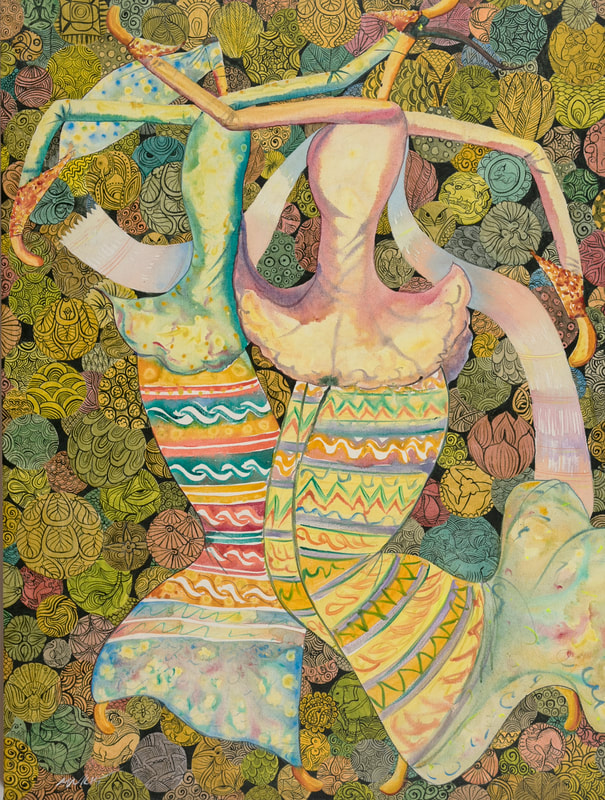

Traditionally, in a rural setting inserted to a daily life activity of chatting near a well in an undisturbed peaceful landscape along the Irrawaddy river of millennial-past central Burma: such as Ba Khine’s Living in Harmony; or Myo Nyunt Khin’s Dancers: positioned before an elaborate pastiched background encompassing dozens of familiar Burmese icons, floral and faunal or a female guardian spirit figure

Let's take a closer look...

In this peaceful landscape scene along the Irrawaddy riverbank in central Burma, aspects of pastoral life and motifs of nature are brightly juxtaposed against harmoniously hued bands of color representing water, rice fields, hills and sky. As a calm serenity, prosperity and stillness arises from the arrangement of planes and flat shapes, there is yet a sense of movement to the right and left, and from the foreground to the background that seems cheerfully animated, conjuring sounds. Three women appear to have drawn water from a communal well and paused for a moment of cordial exchange, while a slight distance beyond, two men and a spirited dog guide an ox-pulled cart through lush paddies. In the far distance at the top of the composition, two boats, one rustic and one engine-driven, glide slowly upstream and downstream on the Irrawaddy, an essential, majestic waterway that rises from the edge of Tibet and transits through Upper Burma downstream to its great delta on the Bay of Bengal. Among distant blue hills, tips of white Buddhist pagodas remind us of the religion that dominates the country. Positioned in the foreground of this glorious vision, the women garner special notice, as though accentuated for their fundamental role in society or steadfast presence in a nostalgic rural life fast disappearing.

Before developing this semi-abstract style, Ba Khine, a self-taught artist, worked for twenty years as a professional photographer, gaining expertise in composition and coloration. He became a fulltime artist in 1996, shown his works internationally since 2006, and is one of the five artists that collectively form the Studio Square Gallery in Yangon.

Before developing this semi-abstract style, Ba Khine, a self-taught artist, worked for twenty years as a professional photographer, gaining expertise in composition and coloration. He became a fulltime artist in 1996, shown his works internationally since 2006, and is one of the five artists that collectively form the Studio Square Gallery in Yangon.

This joyful pair of female and male performers swirl in a traditional dance of the Myai Way era with silk fabrics flying and long-sleeved jackets and longyi flaring. Their expansive torsos and impossibly, curiously tiny heads, hands and feet accentuate a feminine grace, sensuality, and grand energy. Entwined in spirit, movement, courtly costumes, colors, and patterns, the abstracted bodies float before a backdrop filled with carefully drawn motifs associated with Burmese culture.

|

The delicate roundels in the background, so varied in color and pattern, represent ancestral geometric designs or animals—motifs from a thousand-year repertoire of Burmese art. There is the lucky owl, the rabbit associated with the moon, the peacock associated with the sun and more recently the political movement against the military regime, as well as the ogre bilu, empowered to ward off the evil.

When interviewed, Myo Nyunt Khin, who is known for his traditionally-derived iconography in a characteristic pastel palette in homage to a millennium of Burmese art and architecture, said “he most wanted to represent love.” Myo Nyunt Khin graduated from the State School of Fine Arts in Yangon in 1990 and is a fulltime artist in Yangon. The characteristically small heads on his figures once drew suspicion from censors who thought they might be referring to the governing military elite. |

In this section, Burmese women are portrayed...

In an urban setting, where portraits of Burmese feminine beauty are somewhat differently defined in Saw Star’s Look at Us; Min Zaw’s Ordinary People; or Zwe Mon’s Untitled, the only female artist expressing her engaging female gaze with long hair and traditional Burmese features such as using the natural cosmetic thanaka on one’s cheeks; and calligraphic letters sa, da, ba, wa placed in each corner and within the graphic design referring to Buddhism

Let's take a closer look...

This painting prompts reflections on Burmese traditional feminine beauty, female modern existence, vanity, or female emotions veiled behind inscrutable faces. Three young women sport a hairstyle associated with youth and adolescence (yaung pay soo) with hair raised up in a bun. Variations of the hairstyle suggest different ages, as in a young girl’s bun paired with a short bob cut and bangs or a young woman’s hair bun paired with long hair, the “glory of women.” The three faces have different skin tones and large applications of thanaka, a yellowish Burmese cosmetic paste, on their cheeks. The soothing paste, ground from sandalwood (thanaka), is popular even today as a sunscreen and beautifying, fragrant medicinal ointment that goes back some two thousand years. The exquisite touches of jewelry sparkling in the women’s hair reminds us that Saw Star is a jewelry maker himself. They also conjure thoughts of Burmese stories where a woman’s hair comb has significance as a great sentimental possession.

The large eyes, which rise to the fore and stare outward with such steadfast intensity, can play on one’s imagination, prompting thoughts of silent fear, internal resilience, spiritual weariness, quiet thoughtfulness, longing, sadness, or blank vacancy. What are they staring at? Are they silently bearing witness? What are they seeing? How are they responding?

Saw Star created a number of works during this time featuring women whose faces are stretched to fill the canvas and styled with long noses and tiny mouth reminiscent of a Modigliani. Born in Dawei, Tanintharyi Region, he attended the State School of Fine Arts in Yangon and has been participating in group shows in Yangon every year since 2004.

The large eyes, which rise to the fore and stare outward with such steadfast intensity, can play on one’s imagination, prompting thoughts of silent fear, internal resilience, spiritual weariness, quiet thoughtfulness, longing, sadness, or blank vacancy. What are they staring at? Are they silently bearing witness? What are they seeing? How are they responding?

Saw Star created a number of works during this time featuring women whose faces are stretched to fill the canvas and styled with long noses and tiny mouth reminiscent of a Modigliani. Born in Dawei, Tanintharyi Region, he attended the State School of Fine Arts in Yangon and has been participating in group shows in Yangon every year since 2004.

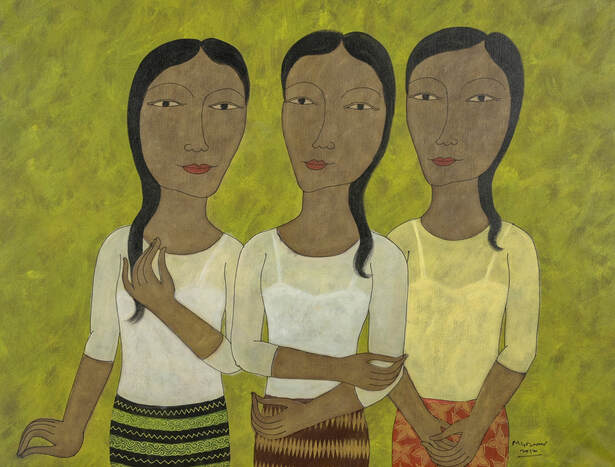

The composition for this painting is intriguingly static and yet animated. The women seem reserved, inscrutable and at the same time modest, kind, alert, and intelligent. They wear the sheer blouse (eingyi) over traditional lace bodices (zar bawli); and native longyi, a traditional garment that is wrapped around the lower body and tied at the waist. In a country that long experienced British colonial occupation, the very act of dressing with a longyi can represent a passive form of resistance or an inherited aspect of the colonial era, but the longyi is also popularly worn today for its practical comfort and beauty.

Like Saw Star’s Look at us, this painting offers a layered nuance of possible meanings. Is the artist commenting on the resilience of “ordinary women” under a half century of dictatorship or celebrating their power and beauty? The subdued nature of the ladies’ facial expressions softened by their strikingly sweet lips, delicate brows, and gentle hand gestures is appealing, yet the eyes stare straight out at us in an insistent manner.

The artist has described the women in his works as being based on traditional Myanmar art in that they do not “highlight what can be seen by the naked eye,” but rather “the emotions behind superficial subjects.” In his interview for Ian Holliday’s book Painting Myanmar’s Transition, Min Zaw said he wants “to show the tender attitude, the soft and honest appearance, the modest and natural life of Burmese women.” Min Zaw was born and educated in Yangon, attending the State School of Fine Arts from 1991 to 1994 and the University of Culture from 1994 to 1998. He is one of the five artists who formed Studio Square in Yangon and has exhibited his works widely, winning an ASEAN Art Award in 2002.

Like Saw Star’s Look at us, this painting offers a layered nuance of possible meanings. Is the artist commenting on the resilience of “ordinary women” under a half century of dictatorship or celebrating their power and beauty? The subdued nature of the ladies’ facial expressions softened by their strikingly sweet lips, delicate brows, and gentle hand gestures is appealing, yet the eyes stare straight out at us in an insistent manner.

The artist has described the women in his works as being based on traditional Myanmar art in that they do not “highlight what can be seen by the naked eye,” but rather “the emotions behind superficial subjects.” In his interview for Ian Holliday’s book Painting Myanmar’s Transition, Min Zaw said he wants “to show the tender attitude, the soft and honest appearance, the modest and natural life of Burmese women.” Min Zaw was born and educated in Yangon, attending the State School of Fine Arts from 1991 to 1994 and the University of Culture from 1994 to 1998. He is one of the five artists who formed Studio Square in Yangon and has exhibited his works widely, winning an ASEAN Art Award in 2002.

Zwe Mon has developed a style that merges a sense of a self-portrait with a wish to symbolize all Myanmar Women. This painting differs from the majority of paintings in this exhibition in that we can contemplate the subject as an image of self-expression unaffected by an imagined male perspective or interpretation. While infused with references to Burmese traditions, the painting alludes to the artist’s personal identity and experiences, as well as her deep hopes for all women in Myanmar.

Burmese traditions can be recognized in the eingyi blouse, cheeks daubed with thanaka sandalwood paste, tidily arranged hair with flowers, and letters from the Burmese alphabet placed in the four corners of the composition. The large eyes seem modeled on the pa ya pite, the classical rendering of eyes in accordance with over a millennium of classical wall paintings in Buddhist temples or the big eyes described in literature that represent honesty. The Burmese letters sa, da, ba, wa situated at each corner of the canvas convey protection, but can also be seen at the center of the symbolic unalome, an iconic spiral design found on the foreheads of Buddha images or used in tattoos as a reference to the Buddhist concept of “conveying a sense of infinity.”

At the same time, the large eyes are also those of the artist. The mole under the figure’s right eye is Zwe Mon’s mole, a beauty mark that can traditionally be associated with bad luck, but to Zwe Mon is something she loves, unaffected by superstition, and something that reminds her that she must not fail. There is no mistaking the hair style and flowers associated with the iconic image of Aung San Suu Kyi and here symbolizing strength and courage. During her interview for NIU, Zwe Mon mentioned the significance of the use of colors, such as “the red background to represent courageous Burmese women.” This symbolism gives rise to new ways to interpret the red coloring of the full lips.

Born in Yangon, educated at the State School of Fine Arts and encouraged by her father, a professional comic artist and illustrator, Zwe Mon nonetheless knows what it is like to suffer discrimination. She fights for the right of women to education and freedom from sexual exploitation, as well as from traditional or modern forms of discrimination.

Burmese traditions can be recognized in the eingyi blouse, cheeks daubed with thanaka sandalwood paste, tidily arranged hair with flowers, and letters from the Burmese alphabet placed in the four corners of the composition. The large eyes seem modeled on the pa ya pite, the classical rendering of eyes in accordance with over a millennium of classical wall paintings in Buddhist temples or the big eyes described in literature that represent honesty. The Burmese letters sa, da, ba, wa situated at each corner of the canvas convey protection, but can also be seen at the center of the symbolic unalome, an iconic spiral design found on the foreheads of Buddha images or used in tattoos as a reference to the Buddhist concept of “conveying a sense of infinity.”

At the same time, the large eyes are also those of the artist. The mole under the figure’s right eye is Zwe Mon’s mole, a beauty mark that can traditionally be associated with bad luck, but to Zwe Mon is something she loves, unaffected by superstition, and something that reminds her that she must not fail. There is no mistaking the hair style and flowers associated with the iconic image of Aung San Suu Kyi and here symbolizing strength and courage. During her interview for NIU, Zwe Mon mentioned the significance of the use of colors, such as “the red background to represent courageous Burmese women.” This symbolism gives rise to new ways to interpret the red coloring of the full lips.

Born in Yangon, educated at the State School of Fine Arts and encouraged by her father, a professional comic artist and illustrator, Zwe Mon nonetheless knows what it is like to suffer discrimination. She fights for the right of women to education and freedom from sexual exploitation, as well as from traditional or modern forms of discrimination.

In this section, Burmese women are portrayed...

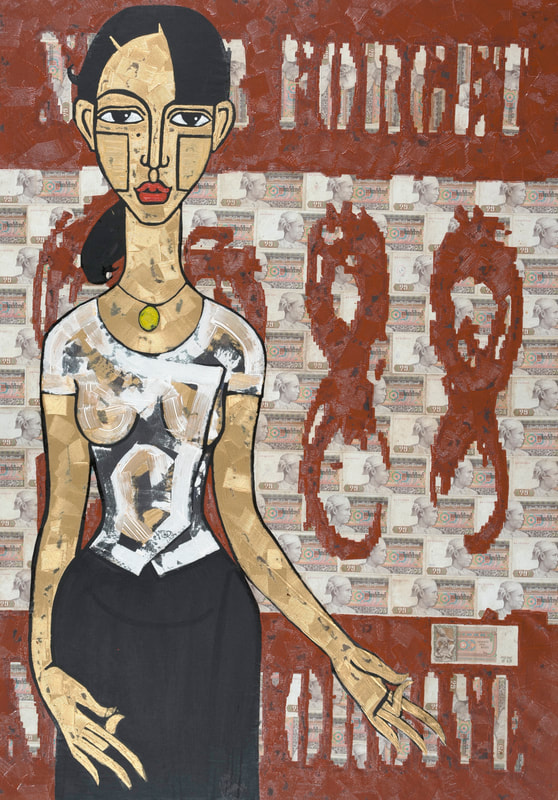

As politically engaged, as in Zwe Yan Naing’s Never Forget —using a collage of demonetized, withdrawn banknotes— in illustrating iconic political figure of Aung San Suu Kyi, and remembering both the long struggle for freedom and the student uprising in 1988 or Myint San Myint’s Protest voicing the revolt of villagers facing the coming of a Chinese Mining company depriving them from their lands.

Let's take a closer look...

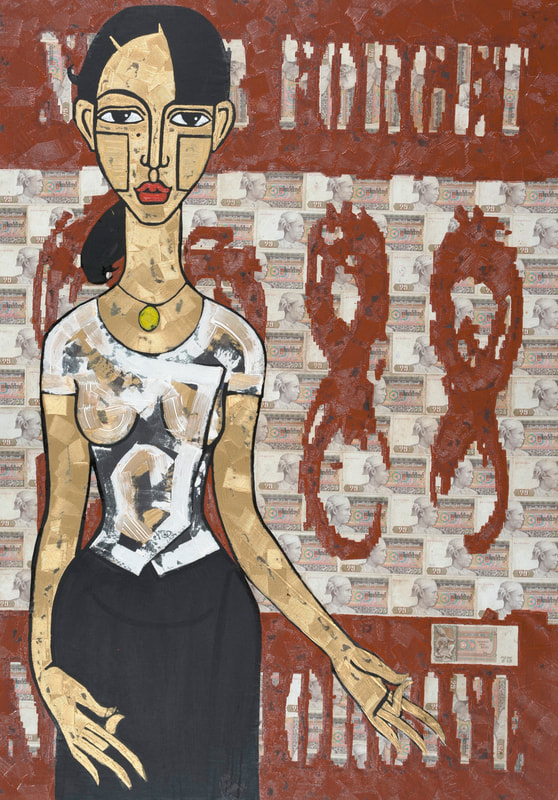

This arresting image of a modern Burmese lady positioned before a background collage of demonetized, de-circulated banknotes with the unusual 75 kyat denomination and glimpses of bold lettering spelling “Never Forget,” “Never Forgive, and “88” in red refers unmistakably to the unforgettable student uprising of 1988 which led to the death and injury of thousands and forced many to flee to neighboring countries.

The woman, no doubt, must refer to Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of Bogyoke Aung San, the “Father of the Nation who was himself assassinated while she was still an infant. This painting presents her as the emerging leader of the National League of Democracy (founded in 1988). Semi-ironically, they displayed a portrait of Bogyoke Aung San even though the 75 kyat banknotes were issued in 1985 to celebrate Burma dictator General Ne Win’s 75th birthday. The banknotes were suddenly invalidated and totally devalued two years later in 1987 leading to widespread bankruptcies amongst that part of the population that held them as cash currency rather than as bank balances.

Since 2011, Zwe Yan Naing is especially well-known for his numerous “currency collages” with historical figures. Born in Rakhine State, he moved to Yangon after living as a monk for nine years in Ngapali and graduated from the State School of Fine Arts in 2009. Having experienced harsh censorship from 2009-2011 when images of Aung Sann Suu Kyi were not allowed (not to mention the color red) Zwe Yan Naing’s art can be seen as a conduit for reminding younger generations not to forget their country’s past heroes, and their legacy to press for more freedom. The artist himself, however, has said in his 2021 interview for Holliday’s book that he is only interested in what he “will discover next” and that he only wants “to pursue tenderness and the depth of art.

The woman, no doubt, must refer to Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of Bogyoke Aung San, the “Father of the Nation who was himself assassinated while she was still an infant. This painting presents her as the emerging leader of the National League of Democracy (founded in 1988). Semi-ironically, they displayed a portrait of Bogyoke Aung San even though the 75 kyat banknotes were issued in 1985 to celebrate Burma dictator General Ne Win’s 75th birthday. The banknotes were suddenly invalidated and totally devalued two years later in 1987 leading to widespread bankruptcies amongst that part of the population that held them as cash currency rather than as bank balances.

Since 2011, Zwe Yan Naing is especially well-known for his numerous “currency collages” with historical figures. Born in Rakhine State, he moved to Yangon after living as a monk for nine years in Ngapali and graduated from the State School of Fine Arts in 2009. Having experienced harsh censorship from 2009-2011 when images of Aung Sann Suu Kyi were not allowed (not to mention the color red) Zwe Yan Naing’s art can be seen as a conduit for reminding younger generations not to forget their country’s past heroes, and their legacy to press for more freedom. The artist himself, however, has said in his 2021 interview for Holliday’s book that he is only interested in what he “will discover next” and that he only wants “to pursue tenderness and the depth of art.

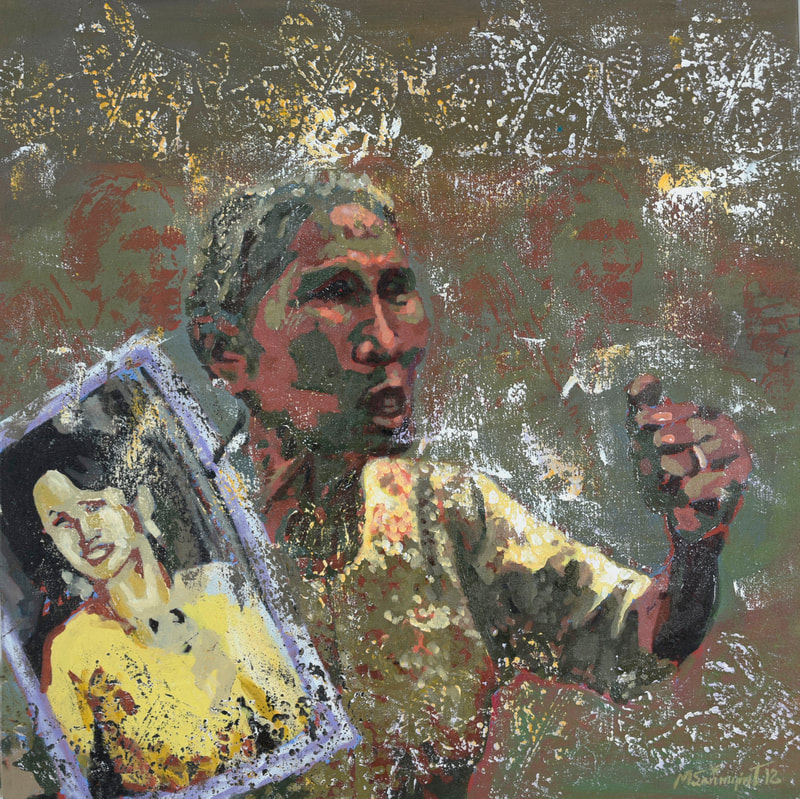

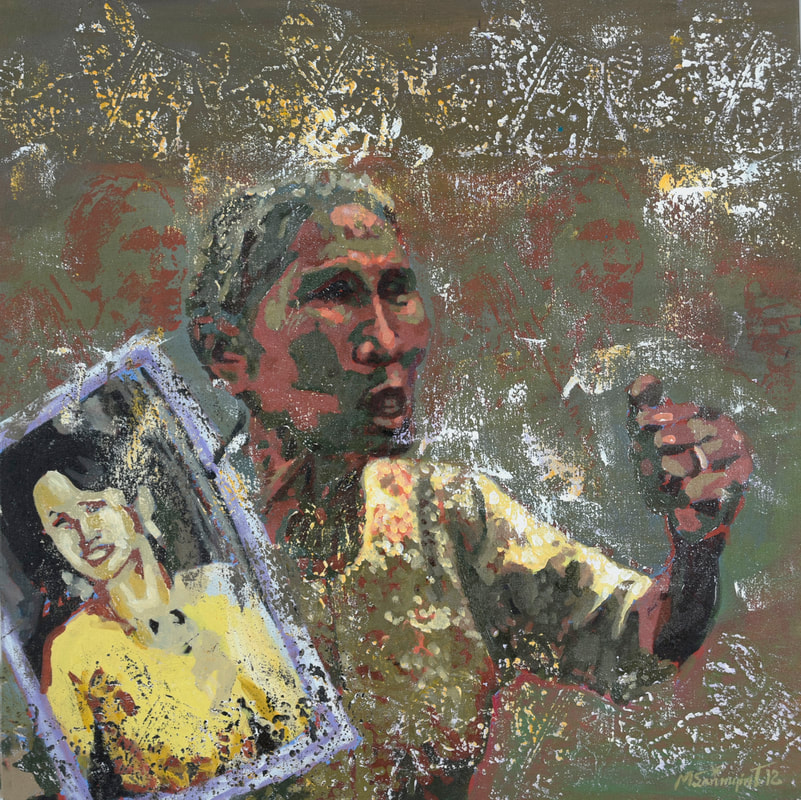

This painting refers to the “Letpadaung Copper Mine” protests against the Chinese mining operation that was initiated following agreements made with the Burmese government. Villagers of Letpadaung accused Wenbao Mining of unfair land confiscations, inadequate compensation, ruined farmlands, and harm to the health of children. The latter half of 2012 witnessed new violence as protestors and rights groups were joined by a surge in villagers and monks. The huge demonstrations forced the Burmese government to reconsider such copper mining concessions allocated to the Chinese.

The raw intensity of this small painting created with silkscreen technique is heightened by knowledge that the artist was responding to contemporary political developments that had just occurred and were not yet resolved. While the image might to be considered an idealization of women’s power and testament to Aung San Suu Kyi’s influence, it is also a memorializing of a very real fight against injustice. Armed with a famous iconic portrait of Aung San Suu Kyi —who was then not yet elected/appointed as State Counsellor—the female villager’s determination and anger is forcefully symbolized by her raised fist, while her fierce face is reproduced multiple times in red in the background, turning it into a ghostly mass of anger. At the top and bottom of the composition, a frieze of smaller reversed images of her protesting form silkscreened in ghostly white fills the air with protesting energy and sounds.

Born in Rakhine State, Myint San Myint graduated from Yangon University and worked as a school teacher in Sittwe, Rakhine State before returning to Yangon in the late 1990s and taking up his father’s profession in silkscreen printing. Once inspired by Gauguin and respecting artists because “they fight for what they believe and what they love,” Myint San Myint has witnessed the developing art scene and opening of galleries in the 2010s but would like to see Myanmar have “a breakthrough in the global art scene” averring, “We’re not an inferior people.”

The raw intensity of this small painting created with silkscreen technique is heightened by knowledge that the artist was responding to contemporary political developments that had just occurred and were not yet resolved. While the image might to be considered an idealization of women’s power and testament to Aung San Suu Kyi’s influence, it is also a memorializing of a very real fight against injustice. Armed with a famous iconic portrait of Aung San Suu Kyi —who was then not yet elected/appointed as State Counsellor—the female villager’s determination and anger is forcefully symbolized by her raised fist, while her fierce face is reproduced multiple times in red in the background, turning it into a ghostly mass of anger. At the top and bottom of the composition, a frieze of smaller reversed images of her protesting form silkscreened in ghostly white fills the air with protesting energy and sounds.

Born in Rakhine State, Myint San Myint graduated from Yangon University and worked as a school teacher in Sittwe, Rakhine State before returning to Yangon in the late 1990s and taking up his father’s profession in silkscreen printing. Once inspired by Gauguin and respecting artists because “they fight for what they believe and what they love,” Myint San Myint has witnessed the developing art scene and opening of galleries in the 2010s but would like to see Myanmar have “a breakthrough in the global art scene” averring, “We’re not an inferior people.”

In this section, Burmese women are portrayed...

As objects of desire like in Hein Thit’s Soft in Line, and Bogalay Kyaw Htoo’s Signs; where the artists used not only the sign language visible with the wrist on the top of the umbrellas but where both artists also expressed the sexualized representation of the body.

Let's take a closer look...

Soft in Line, which reflects a fascination for the female body, plays with abstract expressionist flourishes while utilizing elements of pop culture in the use of bits of printed comic strips and graffiti-like scribbles and sprays of pigment inspired by graffiti on U Bein Bridge. The ample use of red makes a bold statement for artistic and expressive freedom. The artist describes his passion for the female form as something that started when a friend poet studying medicine showed him a book on female genitalia. He said he became “quite overwhelmed by the beauty, nature, dream and passion of women.”

The painting dates to a time when censorship finally began to ease. Until 2013, the military regime forbade anything expressing or inciting political rebellion, and employed harsh censorship banning nudity, abstraction, cartoons, even the use of red, black, or white (because of their potential to suggest blood, violence, good or evil). Essentially anything might be deemed by censors as morally depraved.

Hein Thit’s interest in the work of Egon Schiele and Bagyi Aung Soe suggests an inclination for psychologically intense expressionism and exploration of sexuality. Interestingly, Bagyi Aung Soe’s was deemed “mad” by some because his early works were so shocking, yet he was elevated to the highest echelons of Burmese modern artists after his passing. The shock value of Hein Thit’s steely nonconformist spirit in the use of comics and graffiti-like sprays, as well as playful, exuberant delight in the nude female form reveals the independent spirit of an artist confronting the nature of creation and the very meaning of art. Born in Pyay, Bago Region, Hein Thit graduated from the State School of Fine Arts in 1991, exhibited works locally and internationally, and is one of the five artists who formed Studio Square in Yangon.

The painting dates to a time when censorship finally began to ease. Until 2013, the military regime forbade anything expressing or inciting political rebellion, and employed harsh censorship banning nudity, abstraction, cartoons, even the use of red, black, or white (because of their potential to suggest blood, violence, good or evil). Essentially anything might be deemed by censors as morally depraved.

Hein Thit’s interest in the work of Egon Schiele and Bagyi Aung Soe suggests an inclination for psychologically intense expressionism and exploration of sexuality. Interestingly, Bagyi Aung Soe’s was deemed “mad” by some because his early works were so shocking, yet he was elevated to the highest echelons of Burmese modern artists after his passing. The shock value of Hein Thit’s steely nonconformist spirit in the use of comics and graffiti-like sprays, as well as playful, exuberant delight in the nude female form reveals the independent spirit of an artist confronting the nature of creation and the very meaning of art. Born in Pyay, Bago Region, Hein Thit graduated from the State School of Fine Arts in 1991, exhibited works locally and internationally, and is one of the five artists who formed Studio Square in Yangon.

This curious composition appears to represent a casual line of ladies walking with silk umbrellas drawn.

The title, Signs, draws attention to the surreal depiction of what appears to be a human hand on top of each umbrella offering a coded communication resembling sign language for the deaf. The slender women are reminiscent of young ladies one might see going to a Buddhist temple bearing a traditional food container in one hand while holding a pretty parasol in the other. The view of their lithe bodies —costumed in traditional longyis tied at the waist, and blouses covered with shawls— fades as the row steadily recedes into the distance towards the top.

The composition begs for metaphorical association, but are these ladies slowly moving away or forward? If they represent traditional culture (or their youth, or beauty), are we witnessing their sad disappearance; or their slow, steady march toward the unknown? Are these ladies being ascribed here with a romanticized sensuality which elevates or objectifies them? Or both? Is this a sunny or rainy day? Is the foggy blur permeating the scene a silvery shine or sooty smog? Are we viewing a shining past seen through the fog of today?

The title, Signs, draws attention to the surreal depiction of what appears to be a human hand on top of each umbrella offering a coded communication resembling sign language for the deaf. The slender women are reminiscent of young ladies one might see going to a Buddhist temple bearing a traditional food container in one hand while holding a pretty parasol in the other. The view of their lithe bodies —costumed in traditional longyis tied at the waist, and blouses covered with shawls— fades as the row steadily recedes into the distance towards the top.

The composition begs for metaphorical association, but are these ladies slowly moving away or forward? If they represent traditional culture (or their youth, or beauty), are we witnessing their sad disappearance; or their slow, steady march toward the unknown? Are these ladies being ascribed here with a romanticized sensuality which elevates or objectifies them? Or both? Is this a sunny or rainy day? Is the foggy blur permeating the scene a silvery shine or sooty smog? Are we viewing a shining past seen through the fog of today?

These paintings comprise only a small part of the larger Thukhuma collection, and were recently generously gifted to the Burma Art Collection at NIU in 2019 by Dr. Ian Holliday, scholar and collector during the years of transition (2006-2015), while he was doing his own field research in Myanmar.

Further reading

Visit the Thukhuma Collection to explore a vast collection of contemporary Burmese paintings.

Image Gallery

NIU students and staff explore paintings from this exhibition shown in April 2019 at NIU's Founder's Memorial Library